The opium output of the southeast Asian country has exceeded that of Afghanistan. Afghanistan, where the Taliban banned opium production last year, saw a 95% decrease in cultivation, according to the UNODC.

This year, opium cultivation is estimated to cover 47,100 hectares, up from 40,100 hectares last year. The estimated yield is also up by 36% compared to 2022.

Trend accelerating

“The economic, security, and governance disruptions following the military takeover in February 2021 continue to push farmers in remote areas towards opium cultivation for their livelihood,” said Jeremy Douglas, the UNODC Regional Representative based in Bangkok.

“The intensification of conflict in Shan and other border areas is expected to further accelerate this trend,” he added.

The conflict between the junta and an alliance of well-armed ethnic groups and forces supporting the National Unity Government (NUG) erupted in October and has spread to over two-thirds of the country. The military is reported to have lost key towns.

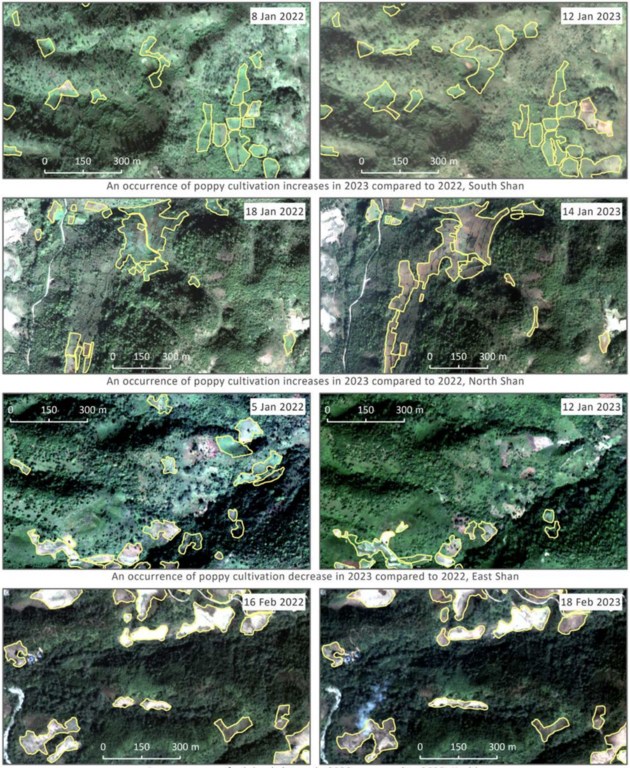

Changes in area under opium cultivation between 2022 and 2023

More sophisticated farming

The UNODC also reported that the most significant increases in opium cultivation were observed in the Shan state, located in the Golden Triangle, a region known for its narcotic production and smuggling. Cultivation in Shan state increased by 20%, followed by Chin and Kachin states, which border India, with increases of 10% and 6% respectively.

The average estimated opium yield per hectare expanded to 22.9 kilograms, surpassing the previous record of 19.8 kilograms set in 2022. This increase reflects the adoption of more advanced farming practices and investments in irrigation systems and fertilizers by farmers and buyers, according to the Office.

Fuelling other crimes

The expansion of opium cultivation is contributing to a growing illicit economy in the Mekong region, which involves high levels of synthetic drug production, drug trafficking, money laundering, and online criminal activities such as casinos and scams.

“The crime and governance challenges in the region are compounded by the crisis in Myanmar. Southeast Asia needs to come together to find solutions to both traditional and emerging threats,” said Mr. Douglas.

The UNODC emphasized the need for solutions that consider the complex realities and vulnerabilities faced by people living in opium-cultivating areas. It also stated that it works directly with farmers and communities to improve socio-economic conditions for long-term income generation and to build resilience to conflict and economic disruptions.